ISSN: 1449-2288International Journal of Biological Sciences

Int J Biol Sci 2005; 1(4):135-140. doi:10.7150/ijbs.1.135 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Ber-H2 (CD30) Immunohistochemical Staining of Human Fetal Tissues

1 Department of Cytology, General Hospital of Chania, Crete, Greece

2 Department of Histology - Embryology, Democritus University of Thrace, Greece

3 Department of Orthopedics, Democritus University of Thrace, Greece

4 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Democritus University of Thrace, Greece

5 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, General Hospital of Alexandroupolis, Greece

6 Department of Dermatology, Democritus University of Thrace, Greece

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: CD30 antigen has long been considered to be restricted to the tumour cells of Hodgkin's disease and of anaplastic large cell lymphoma as well as to T and B activated lymphocytes. It is now apparent that the range of normal and neoplastic cells, which may express CD30 antigen, is much wider than was at first thought. In order to gain insight into the physiological function of CD30 antigen, we studied the distribution of its expression in the tissues of fetuses from week 8th to week 16th.

MATERIALS AND METHODS: We investigated the immunohistochemical expression of CD30 antigen in paraffin-embedded tissue samples representing all systems from 30 fetuses after therapeutic abortion at 8th to 10th and 12th to 16th week of gestation, respectively, using the monoclonal antibody Ber-H2.

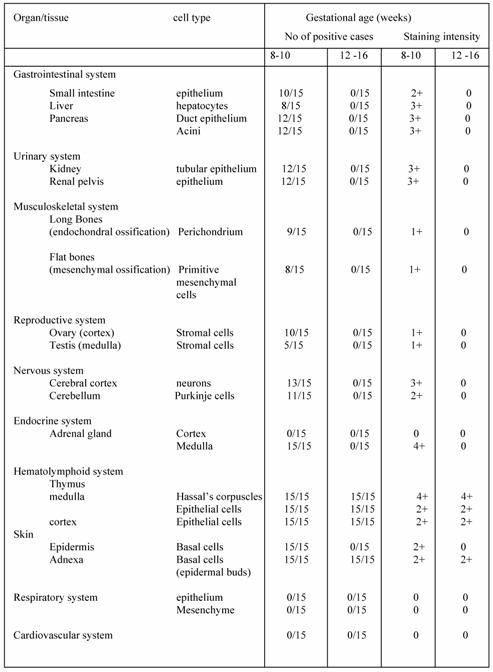

RESULTS: Our results demonstrated that CD30 is expressed early in human fetal development (8th to 10th week of gestation) in several fetal tissues derived from all three germ layers (gastrointestinal tract, special glands of the postpharyngeal foregut, urinary, musculoskeletal, reproductive, nervous, endocrine systems), with the exception of the skin and hematolymphoid system (thymus), in which the antigen is expressed later on (10th week onwards). Expression of CD30 was restricted to the hematolymphoid system in the 12-16 weeks of gestation. No expression of the marker was observed in the respiratory and cardiovascular systems during the entire period examined.

CONCLUSIONS: CD30 antigen is of importance in cell development, and proliferation. It is also pathway-related to terminal differentiation in many fetal tissues and organs.

Keywords: antigen, fetal tissues, 8th-16th week of gestation

1. INTRODUCTION

CD30 antigen, a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily, [1-3] was originally identified as a cell surface antigen on primary and cultured Hodgkin's and Reed-Sternberg cells by use of the monoclonal antibody Ki-1 [4,5]. CD30 antigen normally is expressed by a subset (15–20%) of CD3+ T cells after activation by a variety of stimuli [6]. Its expression is stimulated by interleukin (IL)-4 during lineage commitment of human naïve T cells and is augmented by the presence of CD28 costimulatory signals [7,8]. CD30 also is expressed at variable levels in different non-Hodgkin's lymphomas (NHL) as well as in several virally transformed T and B cell lines [8]. In particular, CD30 is a specific marker of a subset of peripheral T cell NHLs known as anaplastic large cell lymphomas (ALCL) [5]. More recently, CD30 preferential expression has been detected on a subset of tissue and circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells producing mainly Th2 cytokines in immunoreactive conditions [8].

CD30 appears to have an important immunoregulatory role in normal T cell development. Within the thymus, CD30L is highly expressed on medullary thymic epithelial cells and on Hassal's corpuscles [9].

Pallesen and Hamilton-Dutoir [10] were the first to report CD30 expression outside of the lymphoid tissue in 12 out of 14 cases of primary or metastatic embryonal carcinoma (EC) of the testis, by immunostaining with the monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) Ber-H2 and Ki-1. Subsequently, several investigators have confirmed their results and have detected CD30 in these carcinomas at the protein [11-14] and the mRNA level [8]. Two reports demonstrated CD30 expression in 4/21 and 4/63 cases of testicular and mediastinal seminoma, and in the seminomatous components of 7/14 cases of mixed germ cell tumours of the testis, respectively [15, 16]. Suster et al. detected the CD30 antigen in 6/25 yolk sac tumours of the testis and mediastinum [16]. The expression of the CD30 antigen has also been reported in other non-lymphoid tissues and cells, such as soft tissue tumours [17] decidual cells [18,19], lipoblasts [20], myoepithelial cells [21], reactive and neoplastic vascular lesions [22], mesotheliomas [23], cultivated macrophages, and two histiocytic malignancies [24].

The fact that the CD30 molecular can mediate signal for cell proliferation or apoptosis [2] prompted us to perform a systematic investigation of CD30 antigen expression in non hematopoietic embryonal tissues during proliferation and differentiation stages, beginning with the epithelial cells of the developing intestinal crypts [8]. We continued our systematic investigation of the antigen distribution in embryonal tissues using immunohistochemistry, from week 8th onwards, in an effort to uncover patterns of expression that may elucidate the potential role of the marker during development stages.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue Procurement

The tissue material (30 fetuses) used in this study was obtained from the files of the Department of Histology - Embryology at the University of Thrace. Samples representing a wide variety of tissues from all systems were collected from 30 fetuses (15 at 8th to 10th week of gestation and 15 at 14th to 16th, respectively) after therapeutic abortion. The organs used did not show any evidence of morphological abnormality. The Regional Ethics Committees approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals and the procedures followed accorded with institutional guidelines.

Sections of tissue roughly 3-mm thick were fixed in 10% buffered formaldehyde for 7 hours then subjected to routine processing and paraffin embedding. Slides were obtained in all cases, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H-E), PAS, Giemsa and Gomori for morphological evaluation.

Monoclonal antibody and immunohistochemical staining

Antigen retrieval from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue was performed by heating unstained sections immersed in DAKO Target Retrieval Solution (DAKO, Carpintera, CA) according to the manufacture's instructions. A modified labeled avidin-biotin immunohistochemical staining was performed with the use of the LSAB-2 System Peroxidase Kit (DAKO) on DAKO Autostainer, according to the manufacturer's instructions. In short, deparafinized sections were incubated with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 5 min, followed by 10-min incubation with 1:20 solution of Ber-H2 MAb (Novocastra Laboratories Ltd., Newcastle, UK). That was followed by sequential 10-min incubations with a biotinylated link antibody and peroxidase-labeled streptavidin. Staining was completed after a 10-min incubation with DAKO Liquid 3,3'-diaminobenzidine Substrate-Chromogen System utilizing 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen. Biopsied lymph nodes of Hodgkin's disease were used as controls. All cases were coded, and the grading of the immunostaining was performed on a sliding scale of 1+ to 4+ according to the percentage of reactive cells (0 = no staining, 1+ = 1% to 25%; 2+ = 26% to 50%; 3+ = 51% to 75%; 4+ > 76%).

3. RESULTS

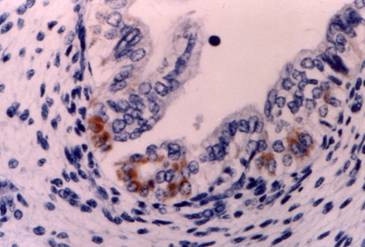

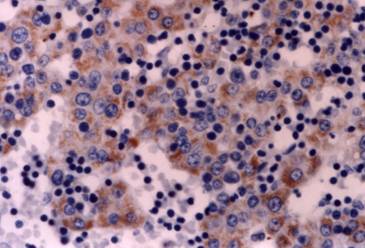

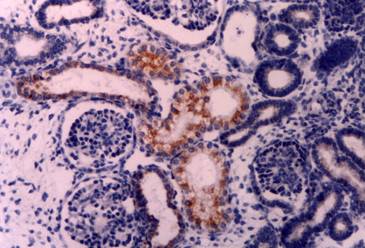

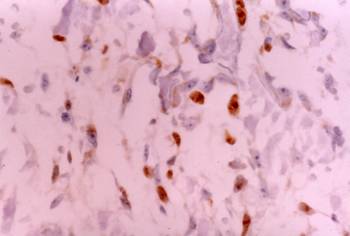

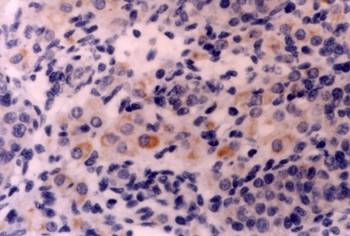

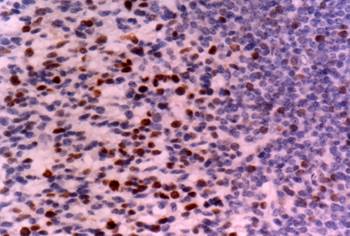

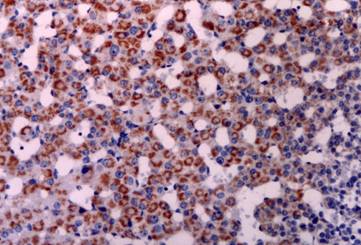

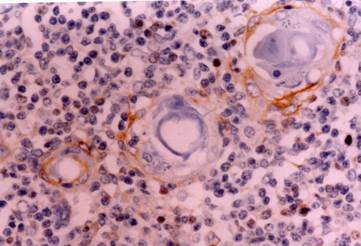

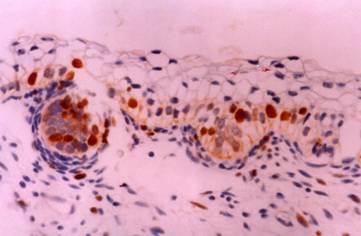

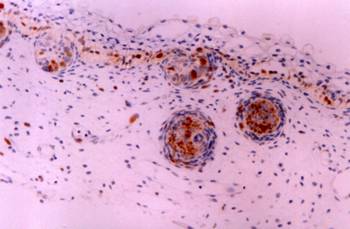

Five microscopic fields of each tissue were evaluated in each case. The results of the immunostaining are summarized in Table 1. Two observers examined the sections independently, and positive cellular staining was manifested as fine brown cytoplasmic granularity and/or nuclear expression. Nuclear expression of the antigen was observed in the case of long bones development during endochondral ossification, and this is a far unreported location of CD30. Maria Trovato et al have reported nuclear expression of CD30 Ligand (CD30L) in oncocytic adenomas of the thyroid [25]. Immunostaining of tissue sections revealed the presence of CD30 antigen in many tissue types in variable abundance, mainly during the first period (8th to 10th week of gestation). Especially, in the gastrointestinal tract, positive staining for CD30 was observed in the epithelial cells (Fig. 1) of the developing primitive crypts (epithelial downgrowths into the mesenchyme between the villi) of the small intestine. For the special glands of the postpharyngeal foregut, a weak cytoplasmic expression of CD30 was noticed in hepatocytes sparing the haematopoietic cells (Fig. 2), whereas a strong positivity was observed in the epithelial cells of the pancreatic ducts and acini. In the urinary system CD30 was expressed in the epithelial cells of the tubules and collecting ducts in the cortex of the kidney (Fig. 3), and in the epithelial cells lining the pelvis. In the musculoskeletal system (long bones), during the process of intracartilagineous (endochondral) ossification, positive CD30 cells were noted in the condensation of mesenchymal cells that constituted the perichondrium of the cartilagenous masses, at the site of the primary ossification centers (Fig. 4). In the intramembranous (mesenchymal) ossification (flat bones), positive CD30 polygonal mesenchymal cells were observed within a loosely organized connective tissue stroma. In the reproductive system in both male and female embryos at 10th week of gestation, staining for CD30 antigen was limited to a population of cuboidal or elongated cells distributed within the cortex for the ovary (Fig. 5), and medulla for the testis In the nervous system (cerebral cortex and cerebellum), CD30 was detected in cerebral cortical neurons (Fig. 6), and Purkinje cells. In the endocrine system (adrenal gland), medullary cells showed a strong cytoplasmic positivity for CD30 antigen, sparing the cortex (Fig. 7). In the haematolymphoid system (thymus), both thymic epithelial cells (TEC) and Hassal's corpuscles in the medulla showed high CD30 expression (Fig. 8). In the thymic cortex, staining was limited to a population of flattened, elongated cells located under the connective tissue capsule of the organ. This is consistent with the observation that human thymus is not completely differentiated before week 13th of gestation, when the corticomedullary junctions and the first Hassal corpuscles become visible. In the skin of the 10-week fetuses, in which the epidermis is comprised of only 2 cell layers, CD30 was expressed in the cells of the basal layer only (Fig. 9). In 16-week fetuses, staining was predominantly observed in the developing skin adnexa (basal cells of epidermal buds), and in occasional basal keratinocytes (Fig. 10).

Other tissues

The immunohistochemical control for the detection of CD30 antigen in the developing respiratory and cardiovascular system was negative.

4. DISCUSSION

The value of the CD30 antigen as a diagnostic marker for Hodgkin's lymphoma and anaplastic large cell lymphoma is well documented [4,5,26]. However, the function of this cytokine receptor in Hodgkin's lymphoma and other CD30-positive diseases is still not clear.

CD30 appears to have an important immunoregulatory role in normal T cell development. In normal cells, this transmembrane glycoprotein can be induced on B and T lymphocytes by mitogen stimulation or viral transformation [8]. cDNA cloning has revealed that the CD30 protein is a cytokine receptor of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily [1,27], the ligand of which belongs to the tumor necrosis factor family [8].

Recent in vitro data indicate that the CD30 receptor-ligand complex can mediate signals for cell proliferation, apoptosis and cytotoxicity in lymphoid cells [29]. During embryogenesis, CD30 could be found in derivatives of all three germ layers; however, this expression was not ubiquitous. Ectodermal derivatives that contained CD30 included cells of the central nervous system, medulla of the adrenal gland, and epidermis [8]. Mesodermal tissues expressing CD30 included kidney, primary ossification centers, and gonads. Intestine, liver, pancreas, and thymus, endoderm-derived tissues, also expressed CD30 antigen [8].

First our findings are of significance with regard to the supported origin of R-S cells. Care must be taken when drawing histogenetic conclusions based on the identification of a single marker in different cell types [8]. Shared expression of CD30 antigen does not necessarily relate Hodgkin and R-S cells to activated lymphocytes [8]. The identification of this antigen in cells as apparently disparate as activated lymphocytes, R-S cells and now human epithelial cells of the developing fetal tissues suggests that previous theories as to the nature of the CD30 antigen must be re-examined. The Hodgkin and Reed-Sterberg cells are indeed lymphocytes as they harbor rearranged immunoglobulin in more than 90% of cases and T cell receptors [28]. Although the expression of CD30 antigen may indicate a relationship between these cell types, it is likely to be less straightforward than was previously supposed. Identification of the normal physiologic role of CD30 antigen is thus made even more imperative if these relationships are to be understood.

A second point is that outside the lymphatic system, CD30 antigen expression in the epithelial cells of developing fetal tissues can mediate signals for cell proliferation and differentiation in a region where other cell types grow throughout life for example in the case of intestinal cryptae cells we refer to stem, goblet, Paneth and enteroendocrine cells [7, 8, 11].

Third, CD30 also appears to be expressed in a selected group of terminally differentiated cells, which are responsive to hormonal stimulation (fetal skin keratinocytes) [12, 16, 17]. This variation of expression suggests a possible role for hormones, preferably progesterone, in the regulation of CD30 expression [17]. This would be a novel mechanism of CD30 induction other than neoplastic transformation and viral infection of lymphocytes. In our previous investigation concerning the developing intestinal crypts, the demonstration of the large Reed-Sternberg like cells in the developing crypts within a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, in the same way that similar Reed-Sternberg like cells are observed in the reactive lymph nodes especially within the parafollicular areas, is evidence that such cells might represent the physiologic counterpart of true Reed- Sternberg cells [8].

Our findings of Ber-H2 staining of fetal tissues and organs could well be added to the list of non- lymphoid tissues and cells normal and neoplastic expressing CD30 antigen. However, it is also possible that the observed staining could represent a false positive reaction related to fixation and paraffin processing, although in the study by Schwarting et al [30] there was generally little difference between the results on frozen and paraffin sections. Nevertheless, in routine diagnostic practice, only formalin-fixed material is generally available for study and thus we conclude that the presence of positive staining cells should not automatically lead to a diagnosis of lymphoma.

The possibility that CD30 antigen is an oncofetal antigen is supported by our positive findings in fetal tissues. We have been able to investigate several tissues from a number of fetuses from 8th gestational week onwards. Pallesen and Hamilton-Dutoit [10] examined CD30 expression in normal adult, neonatal and fetal (week 28) testes, as well as other tissues (brain, spinal cord, lung, gut, kidney, erythropoietic tissue, muscle, bone and connective tissue) from fetuses of 11 and 12 weeks gestational age, with negative results. This is the first demonstration of CD30 in epithelial cells in fetal tissue. Our findings together with reported positive staining seen in placenta [18,19] suggests that the antigen is expressed by epithelial proliferating and differentiating cells of other than lymphoid origin. Clearly the extent of expression of CD30 antigen in embryonal tissues warrants further investigation.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

1. Durkop ABC, Latza U, Hummel M, Eitelbach F, Seed B, Stein H. Molecular cloning and expression of a new member of the nerve growth factor receptor family that is characteristic for Hodgkin's disease. Cell. 1992 ;68:421-427

2. Smith CA, Gruss HJ, Davis T, Anderson D, Farrah T, Baker E, Sutherland GR, Brannan CI, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Grabstein KH, Gliniak B, McAlister IB, Fanslow W, Alderson M, Falk B, Gimpel S, Gillis S, Din WS, Goodwin RG, Armitage RJ. CD30 antigen, a marker for Hodgkin's lymphoma, is a receptor whose ligand defines an emerging family of cytokines with homology to TNF. Cell. 1993 ;73:1349-1360

3. Smith CA, Farrah T, Goodwin RG. The TNF receptor superfamily of cellular and viral proteins: activation, costimulation, and death. Cell. 1994 ;76:959-962

4. Schwab U, Stein H, Gerdes J, Lemke H, Kirchner J, Schaadt M, Diehl V. Production of a monoclonal antibody specific for Hodgkin and Sternberg-Reed cells of Hodgkin's disease and a subset of normal lymphoid cells. Nature. 1982 ;299:65-67

5. Stein H, Mason DY, Gerdes J, O'Connor N, Wainscoat J, Pallesen G, Gatter K, Falini B, Delsol G, Lemke H, Schwarting R, Lennert K. The expression of the Hodgkin's disease-associated antigen Ki-1 in reactive and neoplastic lymphoid tissue: evidence that Reed-Sternberg cells and histiocytic malignancies are derived from activated lymphoid cells. Blood. 1985 ;66:848-858

6. Ellis TN, Simms PE, Slivnick DJ, Jack H, Fisher RI. CD30 is a signal-transducing molecule that defines a subset of human CD45RO+ T-cells. J Immunol. 1993 ;151:2380-2389

7. Nakamura T, Lee RK, Nam SY, Al-Ramadi BK, Koni PA, Bottomly K, Podack ER, Flavell RA. Reciprocal regulation of CD30 expression on CD4+ T cells by IL-4 and IFN-. J Immunol. 1997 ;158:2090-2098

8. Tamiolakis D, Venizelos J, Lambropoulou M, Nikolaidou S, Bolioti S, Tsiapali M, Verettas D, Tsikouras P, Chatzimichail A, Papadopoulos N. Human embryonal epithelial cells of the developing small intestinal crypts can express the Hodgkin-cell associated antigen Ki-1 (CD30) in spontaneous abortions during the first trimester of gestation. Theor Biol Med Mod. 2005 ;2(1):1-6

9. Romagnani P, Annuziatoa F, Manetti R, Mavilia C, Lasagni L, Manuelli C, Vanelli V, Maggi E, Pupilli C, Romagnani S. High CD30 ligand expression by epithelial cells and Hassal's corpuscles in the medulla of the thymus. Blood. 1998 ;91:3323-3333

10. Pallesen G, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ. Ki-1 (CD30) antigen is regularly expressed by tumor cells of embryonal carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1988 ;133:446-450

11. Pallesen G. The diagnostic significance of the CD30 (Ki-1) antigen. Histopathology. 1990 ;16:409-413

12. Ferreiro JA. Ber-H2 expression in testicular germ cell tumors. Hum Pathol. 1994 ;25:522-524

13. De Peralta-Venturina MN, Ro JY, Ordonez NG, Ayala AG. Diffuse embryoma of the testis, an immunohistological study of two cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994 ;101:402-405

14. Latza U, Foss HD, Durkop H, Eitelbach F, Dieckmann KP, Loy V, Unger M, Pizzolo G, Stein H. CD30 antigen in embryonal carcinoma and embryogenesis and release of the soluble molecule. Am J Pathol. 1995 ;146:463-471

15. Hittmair A, Rogatsch H, Hobisch A, Mikuz G, Feichtinger H. CD30 expression in seminoma. Hum Pathol. 1996 ;27:1166-1171

16. Suster S, Moran CA, Domoguez-Malagon H, Quevedo-Blanco P. Germ cell tumors of the mediastinum and testis: a comparative immunohistochemical study of 120 cases. Hum Pathol. 1998 ;29:737-742

17. Mechtesheimer G, Moller P. Expression of Ki-1 antigen (CD30) in mesenchymal tumors. Cancer. 1990 ;66:1732-1737

18. Ito K, Watanabe T, Horie R, Shiota M, Kawamura S, Mori S. High expression of the CD30 molecule in human decidual cells. Am J Pathol. 1994 ;145:276-280

19. Papadopoulos N, Galazios G, Anastasiadis P, Kotini A, Stellos K, Petrakis G, Zografou G, Polihronidis A, Tamiolakis D. Human decidual cells can express the Hodgkin's cell-associated antigen Ki-1 (CD 30) in spontaneous abortions during the first trimester of gestation. Clin Exp Obst & Gyn. 2001 ;28:225-228

20. Sohail D, Simpson RH. Ber-H2 staining of lipoblasts. Histopathology. 1991 ;18(2):191-

21. Mechtesheimer G, Kruger KH, Born IA, Moller P. Antigenic profile of mammary fibroadenoma and cystosarcoma phyllodes. A study using antibodies to estrogen- and progesterone receptors and to a panel of cell surface molecules. Pathol Res Pract. 1990 ;186:427-438

22. Rudolph P, Lappe T, Schmidt D. Expression of CD30 and nerve growth factor-receptor in neoplastic and reactive vascular lesions: an immunohistochemical study. Histopathology. 1993 ;23:173-178

23. Garcia-Prats MD, Ballestin C, Sotelo T, Lopez-Encuentra A, Mayordomo JI. A comparative evaluation of immunohostochemical markers for the differential diagnosis of malignant pleural tumours. Histopathology. 1998 ;32:462-472

24. Anderssen R, Brugger W, Lohr GW, Bross KJ. Human macrophages can express the Hodgkin's cell-associated antigen Ki-1 (CD30). Am J Pathol 134:187-192, 1989. Schwarting R, Gerdes J, Dürkop H, Falini B, Pireli S, Stein H. Ber-H2, a new anti-Ki-1 (CD30) monoclonal antibody directed at a formol-recistant epitope. Blood. 1989 ;74:1678-1689

25. Trovato M, Villari D, Ruggeri R.M, Quattrocchi E, Fragetta F, Simone A, Scarfi R, Magro G, Batolo D, Trimarchi F, Benvenga S. Expression of CD30 ligand and CD30 receptor in normal thyroid and benign and malignant thyroid lesions. Thyroid. 2001 ;11(7):621-628

26. Stein H, Gerdes J, Schwab U, Lemke H, Mason DY, Ziegler A, Schienle W, Diehl V. Intentification of Hodgkin and Sternberg-Reed cells as a unique cell type derived from a newly-detected small cell population. Int J Cancer. 1982 ;30:445-449

27. Beutler B, van Huffel C. Ultraveling fuction in the TNF ligand and receptor families. Science. 1994 ;264:667-668

28. Knowles D, Neri A, Pelicci PG, Burke J, Wu A, Winberg C, Sheibani K, Dalla-Favera R. Immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor B-chain gene rearrangement analysis of Hodgkin disease: Implications for lineage determination and differential diagnosis. PNAS. 1986 ;83:7942-7946

29. Kadin M. Commentary. Regulation of CD30 antigen expression and its potential significance for human disease. Am J Pathol. 2000 ;156(5):1479-1484

30. Schwarting R, Gerdes J, Dürkop H, Falini B, Pireli S, Stein H. Ber-H2, a new anti-Ki-1 (CD30) monoclonal antibody directed at a formol-resistant epitope. Blood. 1989 ;74:1678-1689

FIGURES & TABLE

Small intestine: CD30 expression in the epithelial cells at the bottom of the developing primitive crypts. Immunostain X 200

Liver: CD30 is expressed in liver parenchymal cells, but not in hematopoietic cells. Immunostain X 200

Kidney: CD30 expression in the epithelial cells of tubules and ducts in the fetal kidney (cortex). Immunostain X 200

Intracartilagineous ossification: CD30 positive cells of the perichondrium at the site of primary ossification center Immunostain X 200

Ovary: Cuboidal or elongated CD30 positive cells in the cortex of the ovary. Immunostain X 200

Neural tissue: In the cerebral cortex, CD30 was expressed predominantly by neurons near the surface. Immunostain X 200

Adrenal gland: Note strong staining for CD30 in medullary cells. Immunostain X 200

Thymus: CD30 immunoreactive Hassal's corpuscles in the thymic medulla. Immunostain X 400

Skin: The skin of a 10th week fetus showing restriction of CD30 expression in the basal layer. Immunostain X 200

Skin: The skin of a 16th week fetus showing restriction of CD30 expression in developing skin adnexa (basal cells of epidermal buds), and in occasional basal keratinocytes. Immunostain X 200

Expression of CD30 fetal tissues

Author contact

![]() Corresponding address:

Corresponding address:

Papadopoulos Nikolaos, Ass. Professor in Histology-Embryology, Democritus, University of Thrace, Dragana, 68 100 Alexandroupolis, Greece. Fax: +3025510-30526 E-mail: npapadduth.gr

Received 2005-5-26

Accepted 2005-8-23

Published 2005-10-1